|

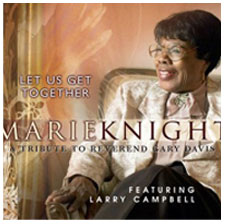

In the first weeks of 1949, a most unusual record entered the top 10 of the R&B singles chart. Titled "Up Above My Head, I Hear Music," it was unquestionably a gospel number, for the singer exclaimed that the celestial notes she heard proved that heaven was waiting for her. But it was also one of the wildest, rockingest tunes of the year. It burst from the gate with a rollicking boogie-woogie piano riff chased by a stinging blues guitar like a hound after a fox. The lead vocal was a piercing soprano that was immediately echoed by a warmer, fuller alto. With each call and response, as if she could hardly wait her turn, the alto crept closer and closer to the soprano, until they were overlapping on the crucial line, "I really do believe there's a heaven somewhere." The effect was exhilarating. The soprano and lead guitarist was Sister Rosetta Tharpe, and the alto was Marie Knight. Although they each had success separately, their greatest moments came on their duets. If "Up Above My Head" represented their commercial peak, their artistic high point was "Didn't It Rain" recorded in the summer of 1947. Once again the pianist was the blues legend Sammy Price, but this time the drummer was Kenny Clarke, the bebop genius who also played with Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk and the Modern Jazz Quartet. This number about Noah and his ark was taken at such a breathless tempo that all the musicians seem to be holding on for dear life. Both Tharpe and Knight got so caught up in the spirit that the normal structure of a call-and-response hymn broke down and their voices got tangled together in impatient, overlapping shouts of "Tell me, didn't it rain-o-rain-o-rain, children, rain, oh my Lord, didn't it, yeah, didn't it, you know it did, didn't it, oh ho, my Lord, didn't it rain?" Fifty-five years later, as Mark Carpentieri of M.C. Records was assembling the tribute album, "Shout, Sister, Shout: A Tribute to Sister Rosetta Tharpe," at the urging of author Gayle Wald he tried to track down Marie Knight to record a new version of "Didn't It Rain." He figured it would give the project an authentic connection to Tharpe, if nothing else. But he was astounded to discover that the 78-year-old Knight was still in terrific voice. Maybe she didn't have her old firepower, but her phrasing was as sharp as a tack and she still had that buttery tone. Because she had never been a huge star, she had never worn her voice out with over-singing. Carpentieri immediately wanted to bring Knight back in the studio to do her own album. But an album of what? It wouldn't make sense to have her remake her old hits, for she could never match the original inspiration of those sides from the '40s, '50s and '60s. Then it came to him in a flash. He would have her sing an album of songs by the Reverend Gary Davis. Davis, Knight and Tharpe had all played gospel music in New York City in the '40s and '50s, but they moved in such completely different circles that Knight had never heard of Davis when Carpentieri first suggested the project. While Knight and Tharpe were having hits on the R&B charts and drawing 27,000 people to a concert at Griffith Stadium in Washington, D.C., Davis was singing on Harlem street corners for tips. While Knight and Tharpe were singing the boogie-woogie style so popular with urban blacks of the day with the help of a rocking band, Davis clung to the ragtime-flavored Piedmont blues of the Carolinas in the '20s and sang solo with his own guitar accompaniment. And yet all three had Southern roots: Davis was born in Laurens, South Carolina, in 1896; Tharpe in Cotton Plant, Arkansas, in 1921; and Knight in Sanford, Florida, in 1925. All three had grown up on the traditions of pre-war African-American gospel music: Davis was an ordained minister; Tharpe got her start in her mama's traveling missionary show; and Knight was a childhood soloist at the Pentecostal Church of God and Christ in Newark. Davis visited New York to make his first recordings in 1935; Tharpe did the same in 1938. Davis moved from Durham, North Carolina, to New York for good in 1944, and a year later Tharpe had her first big hit with "Strange Things Happening Every Day." |

| In 1946, Tharpe met Knight. "I went to a program in a church in New York," Knight remembers, "and Rosetta was on the bill with Mahalia Jackson. That syncopated rhythm Rosetta played on the guitar was very unusual, but it was exciting to me. She heard me on the floor with a group of girls from the church, and she asked if I'd like to sing with her. "She had been looking for a partner, and she thought our voices would go together. She was a soprano and I was an alto, so we had that contrast. She sang lead and I would pick up the second, however I felt it. We were exciting with each other, and the public started looking for the two of us together. I stayed with her 22 years." The duo's first top-20 R&B hit was "Precious Memories" in 1948, followed by "Up Above My Head." Tharpe also recorded definitive versions of such songs as “Nobody's Fault But Mine," "This Train" and "Down by the Riverside," all included on the recent M.C. Records tribute album. Tharpe's version of "Stand By Me” was rewritten by Ben E. King, Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller to become King's 1961 hit of the same title. Knight had her own top-10 hit with "Gospel Train" in 1949, recorded with Sammy Price and the Dependable Boys. She had a secular hit with a remake of Julie London's torch song, "Cry Me a River" in 1965, and the British rock band Manfred Mann remade her 1961 song, "Come Tomorrow." Meanwhile, Davis was discovered by New York's white folk-revival community in the early '50s. He played their concerts in New York, recorded for their labels (Stinson, Folkways, Riverside and Vanguard) and eventually performed at the Newport Folk Festival in 1959, 1965 and 1968. When Peter, Paul & Mary recorded his version of "If I Had My Way" (aka "Samson and Delilah"), Davis was able to buy a house in Queens. Other Davis songs were recorded by the Grateful Dead, Bob Dylan, Dave Van Ronk and Taj Mahal. Davis also gave private guitar lessons to such youngsters as David Bromberg, Stefan Grossman, Janis Ian and the Jefferson Airplane's Jorma Kaukonen. To make Davis's songs come to life, Carpentieri needed a musician who could handle the intricate harmonies and push-and-pull syncopation of Davis's guitar picking. The head of M.C. Records found that player in Larry Campbell. Campbell is best known for playing lead guitar (as well as fiddle, steel guitar, mandolin and banjo) in Bob Dylan's band from 1997 through 2004, but he has also recorded with Willie Nelson, Paul Simon and B.B. King. Campbell has produced albums for Ollabelle and the Dixie Hummingbirds and is working on another for Levon Helm. "I've always been a fan of the Dixie Hummingbirds," Campbell declares, "and Marie sang on some of their recordings. That music is so expressive. It's harmonically simple, but it gets right to the issue musically. There's no gratuitous riffing; it's not about making the stuff complicated just to hear yourself do it. I find with some modern gospel stuff that it becomes more about 'look at me' than 'listen to me.' In the gospel of the '30s through the '60s, you can hear the country and blues and African roots, And that stuff knocks me out. "I tracked down some of Marie's own records, and I was bowled over by her ease of soulful expression; it just flowed out of her. She's one of those singers who just opens her mouth and sings with no pretension behind it. Something about the sound of her voice just sooths me." |

|

Campbell had gone through a phase in the early '70s when he was obsessed with the Reverend Gary Davis. Like many of his fellow baby boomers, his musical tastes traveled a path from the Beatles and the Rolling Stones to Bob Dylan and Pete Seeger to Woody Guthrie and Robert Johnson. He first encountered Davis on Seeger's public-television show, and was so entranced that he immediately bought all the Davis records he could find. He spent hours by the stereo, playing along till he learned every lick.

"The Piedmont blues is more intricate and more syncopated than the Delta blues, which is all a driving 4/4 beat." Campbell argues. "The Piedmont blues is all about imitating ragtime piano playing, with the thumb imitating the left hand of the piano player and the fingers the right hand. The thumb keeps a steady bass line going, and the fingers to either play chords over that or actual melodies. When you alternate between chords and melody enough to give the impression that they're simultaneous, you create the illusion of bass, chords and melody all together."

Knight had never heard of Davis, but when she sat down with Campbell and Carpentieri and listened to the 30 tracks they had picked out, she quickly grew enthusiastic. She said, 'Let's do that' or 'No, I don't want to do that,' and soon they had the 12 tracks on this album. "I listened to it and listened to it," Knight explains, "and some of the songs were very touching. During the recording sessions, though, I did not want to be him; I wanted to do it my own way. I liked the songs but I had to do the arrangements the way they felt right to me. I didn't have to change the lyrics, but sometimes I changed the melody."

Campbell took a very similar approach. "I knew the songs note for

note," he says, "even the mistakes. But what's the point of doing a Rev. Gary Davis imitation? How much can you play like him without sounding just like him only not as good? On the other hand, how far can you stretch it and still call it Rev. Gary Davis style? What I ended up with was a mix of exactly what he did and some with more of myself in it."

Five of the songs – “A Little More Faith," "Samson and Delilah," "I

Feel Just Like Goin' On," "I'll Fly Away" and "Let Us Get Together" – are stripped down to the basics of just Campbell's acoustic guitar and Knight's voice. This minimalist approach gives Knight's voice the most scope and allows her to sing almost conversationally.

"Larry is one of the greatest guitar players I ever worked with,"

Knight says. "He knows music, and he knows how to pick out the parts where the singer should come forward and he should hang back." "This was an opportunity to hear Marie in a totally stripped down musical environment with no frills on it," Campbell adds. "The combination of that guitar style with her voice was an opportunity for her to stand out. I'm always impressed when you cut back on the instrumentation and the person is still able to knock you out. We did a few tunes that we added a bass and drums to, just for variety on the record, but those were still very raw."

The bassist is Lincoln Schleifer, who first played with Campbell in

bluegrasser John Herald's band. Schleifer has since worked with Donald Fagen, Michael McDonald and Boz Scaggs. The drummer is Rich Pagano, who has recorded with Faith Hill, Freedy Johnston and Rosanne Cash. This quartet can be heard on four tracks: "I Am the Light of the World," "You Got To Move," "When I Die I'll Live Again" and "I Belong to the Band." Kim Wilson of the Fabulous Thunderbirds adds bluesy harmonica to two tunes: "Twelve Gates to the City" and "Death Don't Have No Mercy." The latter is the album's centerpiece, a six-minute epic of moaning meditation on death's ruthlessness in this world. On "You Got To Move" and "I Am the Light of the World," Knight, is joined on the vocal by Catherine Russell who has toured and recorded with Rosanne Cash, Steely Dan, Cyndi Lauper, David Bowie, Joan Osborne, The Holmes Brothers and Toshi Reagon.

"Those recordings with Rosetta seemed to be outlined but not arranged," Campbell ventures. "They'd just start singing and see what happened. Marie was the same on this project. We'd run through each song three or four times and she never sang it the same way twice. She'd play with the rhythm; she'd play with the melody. By the third time we played through a song, she'd get real comfortable with the song and start to put herself into the song. You take what you feel in the moment and put that out there. That's what it's all about."

--Geoffrey Himes

Geoffrey Himes has written about music for the Washington Post, the New York Times, Paste, Jazz Times, Country Music Magazine, Rolling Stone and many more for more than 30 years. He is the author of "Born in the U.S.A.," published by Continuum Books in 2005. |